The small hamlet of Fiddletown is resonant with vestiges from its Gold Rush past. Several vintage structures still stand, evoking the time when Fiddletown was a bustling place. As you stroll through the town, imagine what it must have been like with horses and wagons stirring up dust on the unpaved main road, the sounds of hammers striking anvils from numerous blacksmith shops, ladies dressed in finery of the day, men clutching pouches filled with gold dust, merchants inviting you to purchase their wares, music from dance halls and gambling joints, and people speaking German, French, Spanish, Chinese, as well as English in its variant forms.

Fiddletown began as a mining camp during the height of the Gold Rush, with ample placer gold deposits that attracted miners from all parts of the world. The story goes that it was named by early settlers from Missouri who fiddled during slow times when there was no water in the creeks for mining, a frequent occurrence in the summer. Music was always a part of this town, but so was fiddling around.

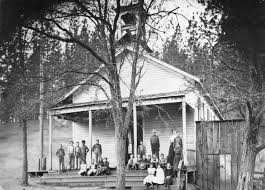

By 1853 Fiddletown had evolved into a trading center for nearby mining camps and for farms in the neighboring Shenandoah Valley. Its commercial area during this period of growth featured fifteen to twenty stores, four hotels, several blacksmith shops, a carpenter’s shop, four taverns, a couple of bakeries, two or three restaurants, dance halls, and even public baths. With a church, post office, and school, it was quite a civilized town. In its heyday, the town’s population was about 2,000.

Fiddletown had one of the larger Chinese communities in the region, comprising about a third of the total population in the 1860 census and eventually about half in the 1880 census. The Chinese population inhabited nearly all of the western part of Fiddletown. Geographically, the town’s population was divided by the small creek lying between the Chinese General Store and the Forge. Europeans and Americans lived to the east of the creek and the Chinese community lived to the west. Only four buildings remain in the Chinese district: the Chew Kee Store, the Gambling Hall, the Chinese General Store, and the Chinese adobe (privately owned).

Fiddletown never developed the deep quartz mines in other parts of the county. By 1878, logging and agriculture took over. The town even lost its identity after a wealthy citizen, Columbus A. Purinton, became embarrassed by the melodious name when signing hotel registers in San Francisco. He and some townsfolk convinced the state legislature to change the name to Oleta, the name of an unidentified woman. This change lasted until 1932 when residents petitioned the U.S. Postal Service to restore the original gold rush name, and so once again, the town became known as Fiddletown.

Fiddletown maintains a rural charm that melds old with new. It lacks retail businesses on Main Street but hosts two active community organizations, the Fiddletown Community Center (www.fiddletownca.org) and the Fiddletown Preservation Society (www.fiddletown.info).